Investment decisions can easily be driven by emotions and chance. Time in the market, rather than timing the market, is far more valuable to investors

Since investors rarely behave according to financial and economic theory, behavioural finance has grown over the past twenty years.

Most investors know that emotion affects the way in which investment decisions are made – and that greed and fear play a large role in driving investment markets. The actions of many investors are based on feelings rather than facts. They may make decisions based on a host of emotional biases that, unfortunately, undermine the chance of meeting the desired investment outcomes.

Admittedly, it is difficult to escape the influence of emotions on investment decision making, and that influence is more than likely the main reason many investors do not achieve the results they want. Our brains regularly set little traps for us – and these ‘emotional potholes’ may have very real costs associated with them. Crucial in overcoming this risk is awareness of how emotions can affect decisions, which may make you a better investor in the process.

In order to improve decision-making and investment results, it certainly helps to be aware of:

- Some of the most common biases

- How to avoid/mitigate these costly investment mistakes; and

- Focusing on your goals

Some of the most common biases

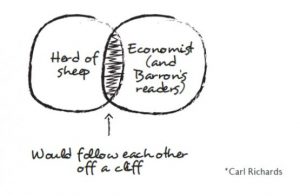

Herd mentality

Our emotions may be influenced by the prevailing investment climate – such as a fear of standing out from the crowd or missing out on a trend. Herd behaviour/mentality can amplify the market upswings and downturns and a prominent example was the dotcom bubble in the late 1990s.

Venture capitalists and private investors made frantic moves to invest huge amounts of money into internet companies, despite the fact that many of those dotcoms not having financially sound business models. Many investors more than likely moved their money in this way, on the reassurance they received from seeing so many other investors do the same thing. They did not want to miss out and followed the ‘herd of sheep’ rather than their logic.

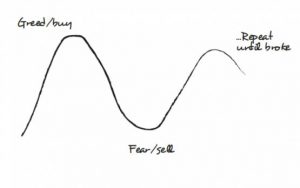

Greed and fear

This relates to an old Wall Street saying that financial markets are driven by two powerful emotions – greed and fear. Succumbing to these emotions can have a profound and detrimental effect on investment outcomes, as too often, investors enter (on greed) or exit (on fear) the market at precisely the wrong time.

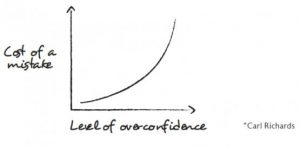

Overconfidence

Overconfidence may cause investors to overestimate the quality of their judgment or information. Some investors believe they can successfully predict market downturns and rallies. Others perceive themselves to have a knowledge advantage when they get a tip from someone in finance or read information from a publication or research report. In reality, several studies have shown that overconfidence bias leads investors to trade more frequently in an effort to align their positions with current market conditions.

The cost of frequent trading erodes returns and returns earned are rarely sufficient to make up the difference. Investors are very susceptible to forgetting the times they were incorrect or recognising the role that luck played in positive outcomes.

If you ever find yourself saying things such as ‘nothing could ever go wrong,’ ‘I believe it will go forever,’ or ‘I know the risks,’ it may be time to check yourself. It is important to remember that every investment carries some risk and the potential for loss.

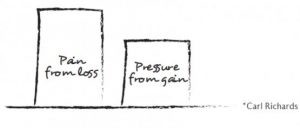

Loss aversion

The basic concept behind loss aversion is that investors feel losses much more than they feel gains. Investors would rather avoid losses than reap rewards. Loss aversion is often seen in financial markets – stock market investors hold their positions with paper losses too long and sell their investment holding paper gains too early.

Consider an investment bought for R1 000 that rises quickly to R1 500. Investors would be tempted to sell it in order to lock in the profit. In contrast, if the investment dropped to R500, investors would tend to hold it, in order to avoid locking in the loss. The idea of a loss is so painful that investors tend to delay recognising it. More generally, investors with losing positions show a strong desire to get back to the break-even point.

This means that investors generally show highly risk-averse behaviour when facing a profit – selling and locking in the sure gain – and more risk-tolerant or risk-seeking behaviour when facing a loss – continuing to hold the investment in the hope the price rises again

Albert Louw is head of business development at Stanlib Multi-Manager.